Macroprudential Diagnostics No. 2

Introductory remarks

The macroprudential diagnostic process consists of assessing the macroeconomic and financial relations and developments that might result in the disruption of financial stability. In the process, individual signals indicating an increased level of risk are detected based on calibrations using statistical methods, regulatory standards or expert estimates. They are then synthesised in a risk map indicating the level and dynamics of vulnerability, thus facilitating the identification of systemic risk, which includes the defining of its nature (structural or cyclical), location (segment of the system in which it is developing) and source (for instance, identifying whether the risk reflects disruptions on the demand or on the supply side). With regard to such diagnostics, instruments are optimised and the intensity of measures is calibrated in order to address the risks as efficiently as possible, reduce regulatory risk, including that of inaction bias, and minimise potential negative spillovers to other sectors as well as unexpected cross-border effects. In addition, market participants are thus informed of identified vulnerabilities and risks that might materialise and jeopardise financial stability.

1 Identification of systemic risks

The increase in economic activity continued in early 2017 at the rate recorded at the end of the preceding year. It was supported by favourable developments in export demand, particularly for tourism services, investments and household consumption. The trend is expected to continue over the remaining part of the year, with the GDP growth rate unchanged from last year (for more information, see Macroeconomic Developments and Outlook No. 2 Following a brief decline in April, the recovery of the production of food products and the consumer confidence index supports expectations according to which the effects of the crisis in the Agrokor Group on economic activity could remain relatively moderate. Nevertheless, the first quarter saw a substantial rise in non-performing loans of banks and related value adjustments.

Structural vulnerabilities of the system as a whole did not change significantly from those analysed in Financial Stability No. 18. This primarily refers to the relatively high public debt-to-GDP ratio. Furthermore, the high level of external debt continues to contribute to the sensitivity of the domestic economy to sudden changes of interest rates, whether caused by a potential rise of reference interest rates or by a significant increase of the country's risk premium (for more details, see Macroprudential Diagnostics No. 1).

Figure 1 Risk map for the second quarter of 2017

Source: CNB (for details on methodology, see Financial Stability No. 15, Box 1 Redesigning the systemic risk map).

Identified structural vulnerabilities of the banking system remained moderate, and its stability satisfactory (for more details, see Financial Stability No. 18, Stress testing of credit institutions). The high level of banking system concentration, increased by the merger of two systemically important institutions[1], as well as the high level of bank exposure concentration (particularly in terms of exposure to the government, as well as to the non-financial corporate sector) remain important sources of banking system structural vulnerabilities. The recent period saw the continuation of the marked rise in the share of kuna loans in total loans, which to some extent alleviated the currency and currency-induced credit risk. However, due to the continued tendency towards long-term savings, mainly in euro, and the increase in the share of deposits in transaction accounts, mainly in the domestic currency, risks associated with the maturity mismatch between assets and liabilities are increasing (for more details, see Financial Stability No. 18, Box 3 Change in the structure of bank funding sources and potential risks to financial stability). In addition, difficulties in the business operations of the Agrokor Group, along with the secondary effects on affiliated businesses, increase credit risk for banks.

The risk assessment for the total non-financial sector (Figure 1, upper left segment) remains unchanged as a result of the uncertainty regarding the outcome of the restructuring of the Agrokor Group currently underway, although recent developments contributed to the containment of systemic risks.

Figure 2 Positive trends in the financial performance of non-financial corporations continue

Notes: The data refer to the performance of enterprises (FINA). Non-consolidated statements for companies in the Agrokor Group are not available for 2016 and are therefore not included in the representation.

Sources: FINA and CNB.

Specifically, risk is gradually decreasing further as a result of the good business performance of the corporate sector (excluding Agrokor) in 2016. Aggregate performance indicators of other corporations in 2016[2] point to the continuation of long-standing positive trends (Figure 2). Operating revenues increased substantially, coming close to the record high of 2008, while earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA) surpassed pre-crisis levels, having increased slightly more than total operating revenues. All of the above positively contributed to corporate net profit, which reached its all-time high since 2007 last year (around HRK 24bn). The decrease in the risk of the non-financial corporate sector is also reflected in the more frequent upgrading than downgrading of corporate credit ratings (see Analytical annex: Measuring rating migration dynamics).

The drop in the debt indicator and the rise in liquid financial assets and disposable income as a result of tax changes and economic recovery contributed to the decrease in the risk of the household sector. In both the household and non-financial corporate sectors, the continued accessibility and affordability of financing decreases the debt repayment burden, which, in turn, contributes to the reduction of interest rate risk. In addition, the currency structure of loans improved as well, as a result of an increase in the share of kuna loans in total loans[3].

Short-term developments in international financial markets remain favourable, affected by the eased financing conditions in the domestic and international financial markets, which, among other things, motivates the ECB to continue to pursue an expansionary monetary policy. At the same time, the domestic financial stress indicator component shrank as a result of diminished volatility on the domestic equity market. However, this is mainly the result of the restriction in the trading of shares of Agrokor Group components imposed by the Croatian Financial Services Supervisory Agency (HANFA), which does not exclude a possible continuation of increased volatility after the restriction is lifted.

2 Potential triggers for risk materialisation

The most pronounced triggers that could lead to the materialisation of certain risks in the domestic economy are related to the non-financial corporate sector, or, more precisely, to the restructuring of the Agrokor Group. Still, in the scenario of successful continued restructuring, the effect on systemic risk indicators in the non-financial corporate sector will not be significant, particularly considering the trend of growing revenues and profit of other non-financial corporations. The majority of restructuring effects will be noticeable at the end of this year and in early 2018, as the primary task so far has been to stabilise business in the short term and ensure current liquidity, while the upcoming period is expected to see settlements with creditors and the financial restructuring of the Agrokor Group.

Figure 3 Risk of contagion related to the cross-border financing of banks is reduced through continued deleveraging of domestic banks with respect to parent banks

Note: The cause of the somewhat more noticeable increase in net foreign assets in Italy in the last two quarters of 2016 is the lending activity of a domestic bank with respect to its foreign owner.

Source: CNB.

Majority foreign ownership of domestic banks, dominated by Italian banks, increases the risk of shock spillover, i.e. of a possible cross-border contagion, which could, for instance, occur in the case of a spillover of negative economic sentiment from the Italian market. Italy's risk premium has been rising continuously since the beginning of 2016, and lately its level has been some 100 b. p. higher than at the beginning of 2016. In the case of Croatia, net positive foreign assets of the banking sector (Figure 3) constitute an important defence against risk spillover, in addition to the new European supervisory framework and the framework for the recovery and resolution of credit institutions. In total, banks registered in the Republic of Croatia currently have higher foreign assets than liabilities.

Figure 4 In spite of positive aggregate net foreign assets of banks, positions by country differ considerably

Notes: The figure shows countries whose share of foreign assets or foreign liablities in total assets or liabilities exceeds 5% as at 31 March 2017. The category "Other" comprises 182 countries.

Source: CNB.

Still, in addition to the aggregate figure, it is important to consider the structure of liabilities as well, i.e. to consider the markets to which domestic banks are exposed when investing their foreign assets and financing their liabilities. In that respect, assets of domestic banks in Italy constitute 12% of total foreign assets, which is not significantly high, while net assets (taking into account the liabilities to Italian residents as well) are significantly smaller and slightly positive (Figure 4).

Divergent monetary policies of leading central banks are another potential trigger for risk materialisation from the external environment. Continued divergence of monetary policies could affect international capital flows and have a negative impact on some emerging markets, particularly in the light of the expected further increase of the Fed's benchmark interest rate in the second half of the current year. This risk is additionally increased by the relatively long period of low interest rates contributing to the underestimation of risks taken on financial markets.

The external environment could also experience a rise in risk aversion and a possible increase in volatility on international markets caused by geopolitical events in the Middle East and their repercussions in Europe. In addition to the above, a possible rise in prices of goods on the global markets could also be a potential trigger; this, in particular, refers to a rise in the prices of energy products resulting from geopolitical instability focused on Qatar. Since the expected primary channel for such events would be the channel of supply on the markets, in the case of Croatia, the net effects of such a rise in prices would be negative (for more details, see the CNB working paper What is Driving Inflation and GDP in a Small European Economy: The Case of Croatia). In the same way, turbulences in international financial markets could be brought about by shifts in the US economic policy and uncertainties regarding the form of Great Britain's exit from the EU.

The aforementioned increase in risk aversion, irrespective of its source, would have the strongest effect on countries with significant accumulated imbalances, such as Croatia.

3 Recent macroprudential activities

3.1 Continued application of the countercyclical capital buffer rate for the Republic of Croatia for the third quarter of 2018

Drawing on a recent analytical assessment of cyclical systemic risk evolution, in June 2017 the CNB announced that the same countercyclical capital buffer rate of 0% would continue to be applied in the third quarter of 2018, i.e. as of 1 July 2018. Specifically, due to the rise in GDP in the first quarter accompanied with the further deleveraging of the non-financial corporate and household sectors, the standardised credit-to-GDP ratio continued to decline, while the credit gap calculated on the basis of this standardised ratio remained negative. Moreover, similar developments were observed in the specific indicator of relative indebtedness as well (based on a narrower definition of credit, including only the claims of domestic credit institutions considered in relation to the quarterly, seasonally adjusted GDP).

3.2 Recommendations of the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) published in 2017 and action based on the recommendations

There were no new recommendations issued by the ESRB in the first half of 2017. A short description of the CNB's activity in line with previous recommendations and of the reports released by the ESRB on the activity of member states in line with two recommendations is provided below.

3.2.1 In June 2017, the CNB reported to the ESRB on the activity in line with Recommendation ESRB/2015/2 on the assessment of cross-border effects of and voluntary reciprocity for macroprudential policy measures and the two amendments to the Recommendation (ESRB/2016/3 and ESRB/2016/4).

Recommendation on the assessment of cross-border effects of and voluntary reciprocity for macroprudential policy measures (ESRB/2015/2) was adopted by the ESRB in December 2015 to ensure that all exposure-based macroprudential policy measures applied in one of the member states are reciprocated in other member states and to encourage member states to assess the cross-border effects of the macroprudential policy measures they apply. The Croatian National Bank implemented the provisions of Recommendation ESRB/2015/2 in its legislative framework by adopting the Decision on the reciprocity of macroprudential policy measures adopted by relevant authorities of other European Union Member States and assessment of cross-border effects of macroprudential policy measures (OG 60/2017).

Recommendation ESRB/2015/2 currently in force has been amended twice in order additionally to reduce potential negative cross-border effects of macroprudential measures.

In March 2016, a measure implemented by the National Bank of Belgium (NBB) was included in the list of macroprudential policy measures recommended to be reciprocated (ESRB/2016/3) pursuant to Recommendation ESRB/2015/2. The measure introduced a five-percentage-point risk-weight add-on for exposures of credit institutions using the internal ratings-based (IRB) approach for mortgage loans granted to Belgian citizens for real estate in the area of Belgium. In June 2017, the Croatian National Bank published a draft of the decision which acknowledges and prescribes the reciprocation of a 5-percentage-point risk-weight add-on for Belgian mortgage loan exposures of credit institutions using the internal ratings-based (IRB) approach. A de minimis exemption from the measure applies to credit institutions whose risk-weighted credit risk exposure to the Belgian mortgage market does not exceed 2% of the share in the portfolio under the IRB approach. In June 2016, at the request of the central bank of Estonia (Eesti Pank) for reciprocation of the adopted systemic risk buffer rate, the General Board of the ESRB decided to include the Estonian measure in the list of macroprudential policy measures recommended to be reciprocated (ESRB/2016/4) under Recommendation ESRB/2015/2. The measure consists of a 1% systemic risk buffer rate applicable to the domestic exposures of all credit institutions authorised in Estonia. In June 2017, the CNB published a draft of the decision acknowledging and prescribing the reciprocation of a 1% systemic risk buffer rate applicable to exposures in Estonia. However, bearing in mind that the CNB already introduced a structural systemic risk buffer for all exposures of credit institutions, this decision will not be applied. Moreover, even if the above mentioned buffer was not applicable to all exposures, a de minimis exemption would apply to credit institutions whose risk-weighted exposures for credit risk do not exceed 2% of total risk-weighted exposure for credit risk in Estonia.

3.2.2 In line with Recommendation ESRB/2015/1 of 11 December 2015 on recognising and setting countercyclical buffer rates for exposures to third countries, in June 2017 the CNB informed the ESRB on its action based on the Recommendation.

The Recommendation of the European Systemic Risk Board of 11 December 2015 on recognising and setting countercyclical buffer rates for exposures to third countries (ESRB/2015/1) provides the rules for identifying material exposure in third countries (countries outside the EU) for the purpose of recognising or setting countercyclical buffer rates. Deciding on countercyclical capital buffer rates for third country exposures is also laid down in the Credit Institutions Act. In line with the Recommendation and the planned schedule, the Croatian National Bank delivered a list of defined criteria for the assessment of the materiality of relevant third countries to the ESRB in late December 2016. In it, the CNB presents the manner of monitoring the risk of excessive credit growth in third countries and the compliance with the principles of public communication pursuant to Recommendation on guidance for setting countercyclical buffer rates (ESRB/2014/1).

At the end of the second quarter of 2017, the CNB assessed material exposure in third countries in line the predefined analytical framework and schedule and established criteria, resulting in the identification of Bosnia and Herzegovina as a material third country for Croatia (for more details, see Box 1). In June 2017, the CNB sent a report with a list of identified countries to the ESRB. The list will be reviewed annually.

Box 1 Identification of Bosnia and Hezegovina as a third country material for the Croatian banking sector

In the second quarter of 2017, the materiality of third countries (countries outside the EU) for Croatia's banking system was analysed in order to determine material exposures in third countries and acknowledge or set a countercyclical buffer rate.

During assessment, the CNB mostly relied on the Decision of the ESRB (ESRB/2015/3). This means that material third countries are identified based on three exposure metrics: original exposures, defaulted exposures and risk-weighted exposures.

The rules determining the materiality of a third country for the Croatian banking sector include several steps ensuring a precise and stable determination of materiality. First, the arithmetic mean of exposures to the third country in eight preceding quarters has to be at least 1% for at least one of the applied metrics, and second, exposures in the past two quarters have to be at least 1% for at least one of the metrics. The country is removed from the list of material third countries if, in twelve preceding quarters, the arithmetic mean of exposures to the country is less than 1% for each of the metrics and if exposures in the two preceding quarters are below 1% for all three metrics. Where countries are on the verge of meeting the materiality criteria, the decision will be based on a detailed analysis of exposures.

At the end of the second quarter of 2017, the CNB assessed material exposure in third countries in line with the analytical framework described above and established criteria, resulting in the identification of Bosnia and Herzegovina as a material third country for Croatia (Table 1).

Table 1 Assessment of materiality of third countries

Note: The table shows the share of exposures in Bosnia and Herzegovina according to the defined metric in the total exposures according to the same metric. The calculations have been made based on available statistical data. The amount of risk-weighted exposures for the private sector is on a non-consolidated basis, while the data used for original exposures and defaulted exposures are shown on a consolidated basis. The last period included in the calculation is the fourth quarter of 2016.

Source: CNB.

Upon determining a material third country, it is necessary to monitor regularly the excessive credit growth in that country, primarily through the analysis of available reports of third-country central banks and macroprudential authorities, or, if necessary, through communication with the competent authorities in the country. Furthermore, the intensity of the risk of excessive credit growth will be analysed using analytical indicators in a risk intensity heat map. Following such analysis, the CNB will decide on the acknowledgement, increase or setting of a countercyclical buffer rate for the material third country.

According to data available for 2016, it is evident that Bosnia and Herzegovina is recording positive rates of growth in lending to both the corporate and the household sector (Figure 5a). Still, the growth thus far recorded cannot be considered excessive, but merely mild or moderate, as confirmed by the analyses of the Central Bank of Bosnia and Herzegovina. At the same time, GDP continued to grow, leading to only a slight increase of the standardised credit-to-GDP ratio to a level above 55% at the end of 2016, while the credit gap calculated on the basis of this standardised ratio remained negative (Figure 5b).

Figure 5 Monitoring credit growth in Bosnia and Herzegovina

a Relative debt indicator (credit-to-GDP ratio) and short-term gap (relative deviation of the ratio from its long-term trend) have been calculated on the basis of a sample from 2009. The quasi-historical gap is calculated on the entire sample, while the recursive gap is calculated on the right-hand side moving sample (of available data for each quarter), with the last observations being always the same for both gap indicators.

Note: The last period included in the calculation is the fourth quarter of 2016.

Sources: Central Bank of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Agency for Statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina and CNB calculation.

The above suggests that the intensity of risk of excessive credit growth is low in Bosnia and Herzegovina (Figure 6). In other words, although Bosnia and Herzegovina recorded a moderate increase in lending activity, there is currently no potential cyclical pressure that would require an increased level of caution from the regulatory point of view.

Figure 6 Risk intensity heat map

Source: CNB.

3.2.3 In March 2017, a report on the compliance of the activity of EU member states with the Recommendation ESRB/2012/2 on funding of credit institutions was released.

In December 2012, the ESRB issued the Recommendation on funding of credit institutions (ESRB/2012/2), with the purpose of incentivising sustainable funding structures for credit institutions and providing implementation guidelines to national macroprudential authorities and the European Banking Authority (EBA) in order to reduce potential systemic risks. Recommendation ESRB/2012/2 was amended on several occasions in order to ensure effective application in EU member states.

In March 2017, the ESRB published a report on the compliance of the activity of EU member states with Recommendation ESRB/2012/2 on funding of credit institutions. The report presents the results of the assessment of the degree to which Recommendation ESRB/2012/2 encouraged concrete regulatory action and the harmonisation of the monitoring of funding risk across EU member states. The CNB submitted the report on the assessment of the results of the implementation of parts of the aforementioned Decision to the ESRB in line with the provided deadlines. The majority of national macroprudential authorities implemented Recommendation ESRB/2012/2 within the time frame provided or during adjustments in the assessment stage. The report states that Croatia fully complies with the provisions of Recommendation ESRB/2012/2.

3.2.4 In February 2017, a report on the compliance of the activity of EU member states with Recommendation ESRB/2013/1 on intermediate objectives and instruments of macroprudential policy was released.

In April 2013, the ESRB issued the Recommendation on intermediate objectives and instruments of macroprudential policy (ESRB/2013/1) in order to increase the efficiency in achieving the ultimate objective of macroprudential policy: decreasing systemic risk and strengthening the resilience of the financial system as a whole. To that end, Recommendation ESRB/2013/1 advises member states and the European Commission to take steps in five key areas, specified as separate parts of the Recommendation: A (definition of intermediate objectives), B (selection of macroprudential instruments), C (policy strategy), D (periodical evaluation of intermediate objectives and instruments) and E (single market and Union legislation).

In February 2017, a report on the compliance of the activity of EU member states with Recommendation ESRB/2013/1 on intermediate objectives and instruments of macroprudential policy was published, assessing the level of implementation of the aforementioned Recommendation by EU member states and the European Commission. The report states that, according to the overall grade, Croatia fully complies with the observed provisions of Recommendation ESRB/2013/1.

3.3 Overview of macroprudential measures in EU countries

EU countries have adopted and put to use the new institutional and technical aspect of capital and liquidity risk management policies in the domestic financial system enabling the prevention, mitigation and avoidance of systemic risks and the strengthening of the system’s resilience to financial shocks. The tables below show macroprudential measures currently applied by EU member states in order to ensure the financial stability of the system (Table 2) and an overview of macroprudential measures applied in Croatia (Table 3), including those outside the CNB's mandate as the macroprudential authority and their amendments from the last issue of Macroprudential Diagnostics.

Table 2 Overview of macroprudential measures in EU countries

Disclaimer: of which the CNB is aware.

Notes: Listed measures are in line with Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 on prudential requirements for credit institutions and investment firms (CRR) and Directive 2013/36/EU on access to the activity of credit institutions and the prudential supervision of credit institutions and investment firms (CRD IV). A list of abbreviations and their explanations is provided at the end of the publication. Measures that have been activated since the last table was published are shown in green, while yellow indicates measures that have been supplemented or corrected from the last version of the table, which was compiled based on information available up to November 2016.

Sources: ESRB, CNB, notifications from central banks and web sites of central banks as at 1 July 2017.

Table 3 Implementation of macroprudential policy and overview of macroprudential measures in Croatia

Note: A list of abbreviations and their explanations is provided at the end of the publication.

Source: CNB.

Analytical annex: Measuring rating migration dynamics

During the last period of recession, a significant portion of credit risk to which financial institutions were exposed materialised, particularly with regard to the non-financial corporate sector. Credit risk materialised in relation to corporations which ran into financial difficulties and were unable to settle their due loan obligations to credit institutions. On the other hand, even corporations that continued to regularly settle their due obligations saw structural deterioration in their financial statements, which negatively affected balance sheet ratios, eroding their creditworthiness and increasing their level of risk.

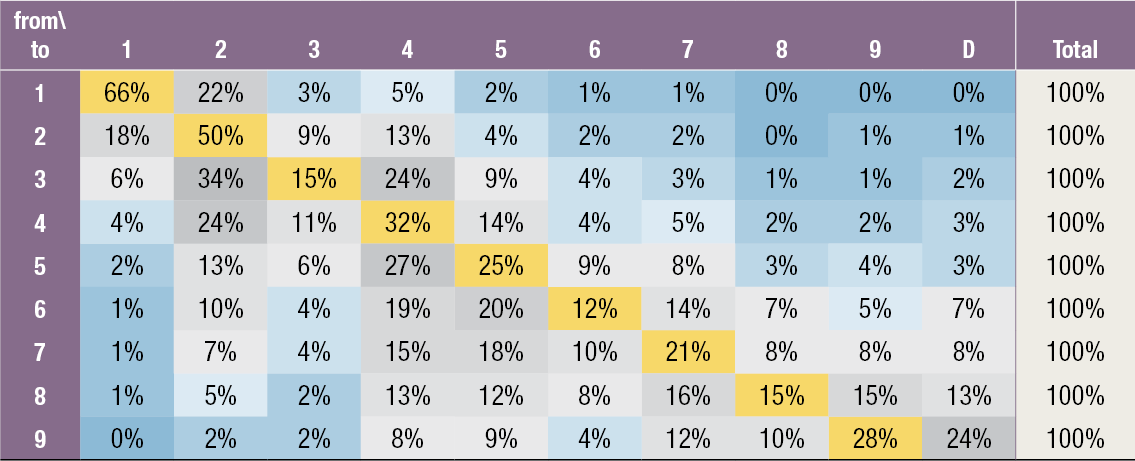

The Croatian National Bank developed an internal rating system to assess the probability of default for the non-financial corporate sector based on indicators from annual financial statements of enterprises and behavioural variables from business relations of corporations with credit institutions. The internal rating system has nine rating classes for corporations settling their obligations and one rating class (D) for corporations in default. From the financial stability point of view, it is possible to use volatility within the rating system to gain additional insight into risks to which the financial system would be exposed in the event of a recession and to assess how fast an improvement in credit quality could be expected in the non-financial corporate sector following economic recovery. Rating migration matrices analysed in the manner described above provide an additional tool to determine the direction and dynamics of change in the degree of risk in the non-financial corporate sector by aggregating effects from the micro-level of individual corporations to the macro-level of the riskiness of the entire sector with a dynamic component.

Rating migration matrices observe changes in corporate ratings over two consecutive periods. In this analytical annex, a method which shows the change of the initial rating relative to the rating given at the end of the observed period (in this case, one year) is used. Initial ratings are provided in rows, and final ratings in columns, ranked from the highest to lower ratings. Changes are relative with regard to the initial rating, so that the sum of all rating migrations in a row equals 100% and represents the probability of a change of rating from the initial one (row) to one of the final ones (column), including the default status (column D). The matrix diagonal represents stable ratings, i.e. those that do not change within the observed period. Credit risk materialisation is considered to occur in corporations entering default (under the Basel III definition), i.e. in those rated "D", while an increase in the level of risk is shown by the migration of ratings above the matrix diagonal.

Table 4 One-year rating migration matrix of corporations (by number) – 2011–2012

Note: The migration matrix shows one-year rating migrations in 2012.

Source: CNB calculation.

Table 5 One-year rating migration matrix of corporations (by number) – 2015–2016

Note: The migration matrix shows one-year rating migrations in 2016.

Source: CNB calculation.

Using the measure of rating change[4] representing the average probability of rating change weighted by the intensity (number) of changes in all corporations included in the matrix over the period of one year, it is possible to gain an insight into average developments at the non-financial corporate sector level (Figure 7).

Figure 7 Average migrations of the number of corporations by years and segments (MSVD)

Notes: ML refers to the medium-sized and large enterprise segment, S to the small enterprise segment, and "All" to both segments. Years in the figure denote the initial year in migration matrices (31.12.T0)/the final year (31.12.T+1), according to which the final rating was calculated based on the report from year T+1.

Source: CNB calculation.

Figure 7 shows that the performance of medium-sized and large enterprises was less volatile than the performance of small enterprises and that it stabilises faster through gradual economic recovery.

However, the measure thus defined provides no information on the direction of rating movement, i.e. on what is faster – rating upgrade or downgrade. If the measure is modified by calculating the difference of the part of the matrix above the diagonal (rating downgrade) and the lower part (rating upgrade), it is possible to examine whether ratings erode faster than they recover or vice versa. On the basis of calculated "net" migration matrices (Figure 8), it is evident that, in the recent period, there is a tendency of net rating upgrade (migration table positive asymmetry).

Figure 8 Average "net" migrations of the number of corporations by years and segments (MSVD)

Notes: ML refers to the medium-sized and large enterprise segment, S to the small enterprise segment, and "All" to both segments. Years in the figure denote the initial year in migration matrices (31.12.T0)/the final year (31.12.T+1), according to which the final rating was calculated based on the report from year T+1. The "net" measure is calculated as the difference of MSVD rating upgrade and downgrade measures.

Source: CNB calculation.

The higher sensitivity of rating change in the medium-sized and large enterprise segment to economic developments in the initial stage of economic recovery suggests that this segment provided initial momentum to the exit from recession, while ratings in the small enterprise segment follow the recovery of the medium-sized and large enterprise segment with a phase shift due to business interactions. Moreover, the continued increase in the dynamics of rating recovery in the small enterprise segment is based on the interaction with medium-sized and large enterprises.

Glossary

Financial stability is characterised by the smooth and efficient functioning of the entire financial system with regard to the financial resource allocation process, risk assessment and management, payments execution, resilience of the financial system to sudden shocks and its contribution to sustainable long-term economic growth.

Systemic risk is defined as the risk of an event that might, through various channels, disrupt the provision of financial services or result in a surge in their prices, as well as jeopardise the smooth functioning of a larger part of the financial system, thus negatively affecting real economic activity.

Vulnerability, within the context of financial stability, refers to structural characteristics or weaknesses of the domestic economy, which may make it less resilient to possible shocks or intensify the negative consequences of such shocks. This publication analyses risks related to events or developments that, if materialised, may result in the disruption of financial stability. For instance, due to the high ratios of public and external debt to GDP and the consequentially high demand for debt (re)financing, Croatia is very vulnerable to possible changes in financial conditions and is exposed to interest rate and exchange rate change risks.

Macroprudential policy measures imply the use of economic policy instruments that, depending on the specific features of risk and the characteristics of its materialisation, may be standard macroprudential policy measures. In addition, monetary, microprudential, fiscal and other policy measures may also be used for macroprudential purposes, if necessary. Having in mind that despite certain regularities, the evolution of systemic risk and its consequences may be difficult to predict in all of their manifestations, the successful safeguarding of financial stability requires not only cross-institutional cooperation within the field of their coordination, but also the development of additional measures and approaches, when needed.

| Art. | Article |

| bn | billion |

| b.p. | basis points |

| CB | capital conservation buffer |

| CCB | countercyclical capital buffer |

| CHF | Swiss franc |

| CNB | Croatian National Bank |

| CRD IV | Directive 2013/36/EU on access to the activity of credit institutions and the prudential supervision of credit institutions and investment firms |

| CRR | Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 on prudential requirements for credit institutions and investment firms |

| d.d. | dioničko društvo (joint stock company) |

| DSTI | debt-service-to-income ratio |

| EBA | European Banking Authority |

| EBITDA | earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation |

| ECB | European Central Bank |

| ESRB | European Systemic Risk Board |

| EU | European Union |

| Fed | Federal Reserve System |

| FINA | Financial Agency |

| GDP | gross domestic product |

| G-SII | global systemically important institutions buffer |

| HANFA | Croatian Financial Services Supervisory Agency |

| HRK | Croatian kuna |

| IRB | internal ratings-based |

| LGD | loss-given-default |

| LTD | loan-to-deposit ratio |

| LTI | loan-to-income ratio |

| LTV | loan-to-value ratio |

| NBB | National Bank of Belgium |

| no. | number |

| OG | Official Gazette |

| O-SII | other systemically important institutions buffer |

| O-SIIs | other systemically important institutions |

| Q | quarter |

| SSRB | structural systemic risk buffer |

Two-letter country codes |

|

| AT | Austria |

| BE | Belgium |

| BG | Bulgaria |

| CY | Cyprus |

| CZ | Czech Republic |

| DE | Germany |

| DK | Denmark |

| EE | Estonia |

| ES | Spain |

| FR | France |

| GR | Greece |

| HR | Croatia |

| HU | Hungary |

| IE | Ireland |

| IT | Italy |

| LT | Lithuania |

| LV | Latvia |

| LU | Luxembourg |

| MT | Malta |

| NL | The Netherlands |

| NO | Norway |

| PL | Poland |

| PT | Portugal |

| RO | Romania |

| SE | Sweden |

| SI | Slovenia |

| SK | Slovakia |

| UK | United Kingdom |

-

The group of credit institutions comprising Splitska banka and OTP banka will operate as separate business and legal entities until the end of the first half of 2018. ↑

-

Annual financial data of enterprises for 2016 do not include financial statements of the Agrokor Group due to the restructuring and audit process. ↑

-

At the end of March 2017, an increase of approximately six percentage points was recorded in the share of kuna loans in total loans to the aforementioned sectors on an annual level. ↑

-

Jafry, J., and T. Schuermann (2004): Measurement, estimation and comparison of credit migration matrices, Journal of Banking and Finance. ↑