The outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic and uncertainty about its effects on the economy have refuelled fears of the depreciation of the kuna and strengthened the tendency to hold foreign currency. This has reversed the years-long downward trend of the euroisation of the banking system. If the growth of foreign currency deposits continues, it does not necessarily have to trigger depreciation pressures, as was the case in March this year, but it may reduce the availability of kuna loans because banks might turn to granting indexed loans.

In countries with a deeply rooted euroisation[1], such as Croatia, the economic crisis sharply increases distrust in the stability of the domestic currency among households. The fear of depreciation may prompt people to withdraw funds (which are predominantly in foreign currency) from banks and other financial institutions or convert their kuna savings with banks to foreign currency. In both cases demand for foreign currency rises, thus causing depreciation pressures, which can actually contribute to the materialisation of households' concerns about depreciation. In other words, savers’ behaviour may contribute to the realisation of their fear – the weakening of the kuna. Banks are the channel through which such a process takes place as they, faced with the growth of the share of foreign currency deposits in their liabilities, tend to increase the share of foreign currency in their assets. The manner in which banks react is usually twofold: first is to increase foreign assets, for which banks must obtain foreign currency and thus create additional demand for foreign currency while stimulating the weakening of the kuna. The other way is to intensify the granting of indexed loans and reduce the supply of kuna loans. However, the latter option does not require banks to purchase foreign currency on the market. Considering the different implications of the two strategies on foreign currency demand, it is interesting to compare the developments of banks’ deposits and assets during the global financial crisis of 2008 with the recent developments in 2020.

Fear of depreciation of the kuna drives the substitution of kuna by foreign currency deposits

onset of the global financial crisis in September 2008 led to a strong, but temporary withdrawal of household deposits from banks, while in the crisis caused by the coronavirus it was not the case. In October 2008, household deposits with banks fell by as much as HRK 5.4bn, but their outflow was soon halted, after which depositors returned their savings to the banks, but mostly in foreign currency. In contrast to 2008, in March 2020, when the pandemic started to have a more considerable impact on Croatia, total household deposits with banks jumped by a high HRK 2.1bn and total deposits of all sectors by HRK 4.9bn, three times more than the average monthly growth in the previous year.[2] Deposits continued to grow in April, although at a more moderate pace. This confirms that households today have more confidence in the stability of the banking system than twelve years ago. ir confidence is justified, since the origin of this crisis is not in the financial system, by contrast to the previous one, and banks today are also even better capitalised, they rely on more stable sources of financing (domestic deposits, not external debt) and are more hedged against risks (they reserve more funds for potential losses from non-performing loans and their debtors are less exposed to exchange rate and interest rate risks due to the larger share of kuna loans and loans granted with a fixed interest rate).

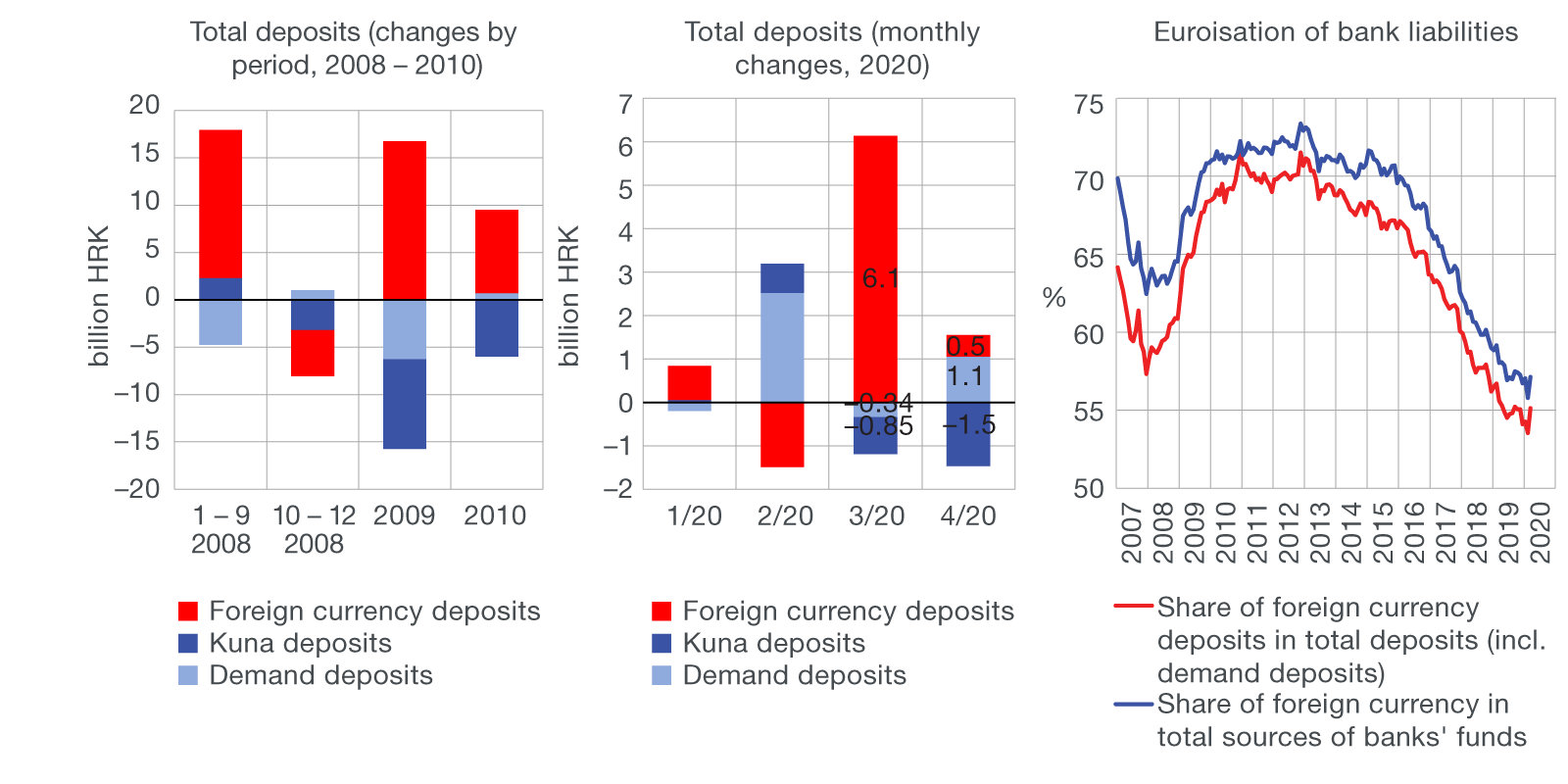

Although the outflow of deposits from banks was avoided, the tendency to hold foreign currency (particularly the euro) strengthened again due to the fear of depreciation. Domestic sectors’ foreign currency deposits in March and April 2020 increased by HRK 6.6bn[3], while kuna deposits decreased by HRK 1.6bn (including demand deposits, i.e. current and giro account balances) (Figure 1, centre). Consequently, the share of foreign currency in total bank funding sources increased from 55.8% at the end of February to 57.3% at the end of April (Figure 1, right). During the previous crisis, households and other domestic sectors substituted kuna by foreign currency deposits throughout 2009 and to a lesser extent in 2010 (Figure 1, left). The share of foreign currency deposits in total bank funding sources then increased from 63% in September 2008 to 72% in December 2010.[4] If trends from the previous crisis repeat in this crisis, the increase in the deposit euroisation could also be expected to continue in the coming months.

Figure 1 Development of deposits with banks and deposit euroisation

Notes: The first two figures show transactions that do not include the effect of the exchange rate on the development of deposits. The banks’ funding sources include demand deposits, foreign currency deposits, kuna savings and time deposits and foreign liabilities. In addition to deposits with banks, the data also include deposits with savings banks, housing savings banks and money market funds.

Source: CNB.

Banks react to the growth of foreign currency deposits by placing foreign currency abroad and granting indexed loans on the domestic market

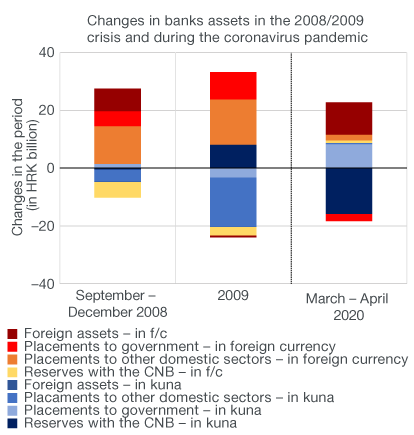

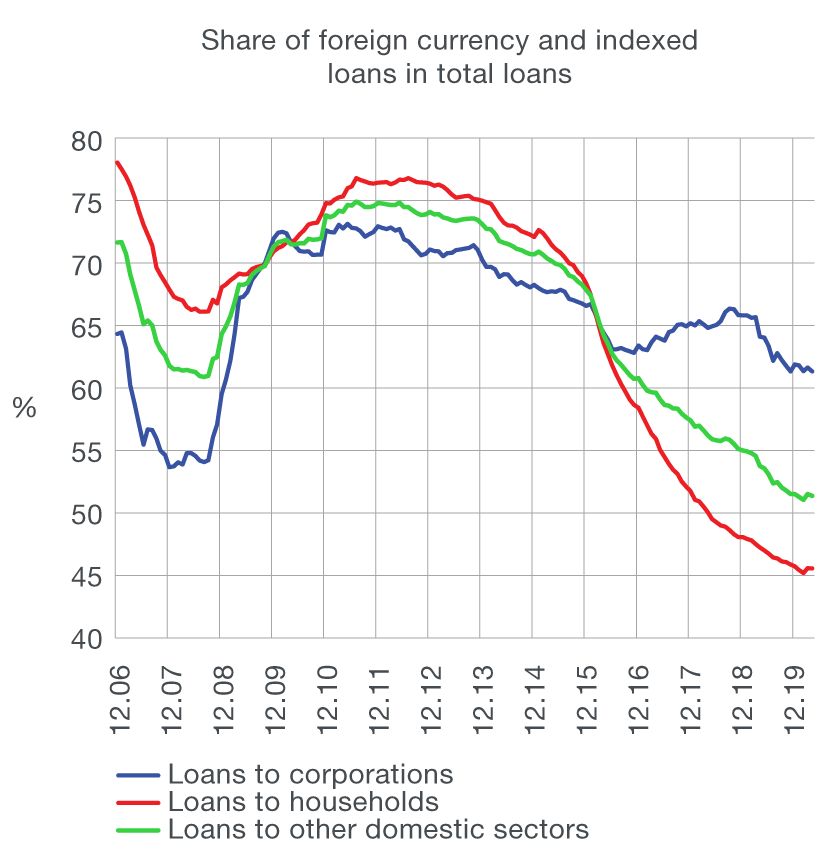

Banks adjust the currency structure of their balance sheet assets and liabilities to hedge against exchange rate risk. For this reason, the described changes in the currency structure of deposits (liabilities) forced banks to make changes in the currency structure of their assets. During the previous crisis, banks reacted in two ways, with different implications on monetary policy. First, they increased foreign assets, mostly by placing abroad foreign currency obtained from the CNB’s foreign exchange interventions (Figure 2). The increase in foreign assets creates foreign currency demand, which in principle can only be met by the central bank’s exchange rate interventions. However, the growth of foreign assets was short lived, and in February and March 2009, banks reduced foreign assets using foreign currency to repay their external debt. At the same time, banks took up a different strategy and intensified lending with a currency clause. The re-euroisation of loans was more pronounced in corporate loans, but that was halted in early 2010, while the re-euroisation of household loans continued until mid-2011 (Figure 3). Switching to a different balance sheet adjustment strategy was time consuming because banks could not change credit policies or grant larger loan amounts overnight. However, it eventually reduced foreign currency demand and the needs for CNB’s interventions because loan indexation enabled the adjustment of the currency structure of the balance sheet without the need for banks to purchase foreign currency on the market.

| Figure 2 Changes in banks' assets | Figure 3 Euroisation of loans |

|

|

Note: Placements to other banking and non-banking financial institutions are not shown because data on their currency structure before December 2010 are not available.

Source: CNB.

With regard to the recent crisis, in March and April 2020, banks again first strongly increased their foreign assets, using foreign currency funds purchased from the CNB. In the two months, banks placed about EUR 1.4bn or HRK 11.2bn abroad (Figure 2). However, it is worth noting that banks' net foreign position today is much more favourable than in 2009, with very low debt levels towards foreign creditors. Therefore, this time around, no significant external debt repayments are expected. In addition, returns on investments abroad are very low, which may deter banks from a long-term reliance on this balance sheet adjustment strategy.

Possible reduction in the availability of kuna loans

The share of foreign currency and indexed placements to corporations and households increased in March and April this year, which contributed to the adjustment of banks' currency position, but also stopped the years-long decline in credit euroisation (Figure 3). However, it was not caused by banks’ active measures, but by the depreciation of the kuna, which increased the kuna value of the existing foreign currency and indexed placements. When looking at the transactions data (not including the effect of the exchange rate changes), kuna placements in the two months actually grew more than foreign currency placements.

To conclude, the experiences from the previous crisis indicate that banks first react to the sudden rise in foreign currency deposits by increasing foreign assets, which raises foreign currency demand and creates pressures on the depreciation of the kuna, and then later gradually adjust the currency structure of domestic loans. The reason for that is the time required to adjust credit policies and procedures and the loan supply. Therefore, if the upward trend in foreign currency deposits continues, availability of kuna loans could be reduced in the coming months because banks might turn to indexed loans, which would eliminate the source of depreciation pressures recorded in March this year.

The term euroisation implies the use of the euro instead of the domestic currency for different functions of money, such as the measure of value (real estate, car prices, etc.) or a means of saving (foreign currency deposits and cash). ↑

-

Some of the increase in deposits in March most likely referred to the inflow of funds from investment funds because investors intensively withdrew their shares/units from investment funds, in particular from bond funds. For more details, see https://www.hanfa.hr/vijesti/konzervativni-ulagatelji-reagirali-na-pandemiju-koronavirusa-zna%C4%8Dajnim-povla%C4%8Denjem-iz-ucits-fondova/ (only in Croatian).↑

-

The data refers to the transaction-based growth of foreign currency deposits, i.e. excluding the effect of exchange rate growth. Domestic sectors include enterprises, households and financial institutions, except credit institutions and money market funds. ↑

-

The increase in euroisation in 2008 was preceded by the trend of pronounced de-euroisation of deposits during 2006 and 2007, driven by the appreciation of the kuna due to large capital inflows and favourable macroeconomic developments, as well as monetary and macroprudential policy measures directed at the strengthening of banks’ resilience to exchange rate risk. ↑